The Color of Law & The Address Book July 9, 2020

The following post includes affiliate links. More details here.

Can Haz Data? If you haven’t completed our reader poll, now is the time! The poll will close at noon on Sunday, July 12, and we’d love to hear from you before then! If you’re reading this, your opinion matters! If you love data, please give us some of that love! Thanks to our dear readers who’ve already completed it, especially if it was for my birthday!.

Want to read with us?

Virtual Book Club Part Trois: Join us on Friday, August 7 at 7:30 p.m. CST for a discussion of The Care and Feeding of Ravenously Hungry Girls by Anissa Gray. The Kindle edition of this title is still on sale for $2.99! If you’re interested, registration is open here.

We are still working through, one day at a time, Layla F. Saad’s Me and White Supremacy and encourage others to join us. Overdrive/Libby users can still check out a copy for a few more days without a waitlist, along with a couple of other social justice titles in audiobook or e-book format.

How many book clubs do you need? MORE! Just kidding, but we’re feeling good about two. Join us in joining ReadaBookwithKara to read and discuss Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston. If you too would like to Read a Book! With Kara, check out the details here, put the August 1 livestream discussion on your calendar, and then read some of Kara’s work here.

And now for your regularly scheduled book talk, times two!

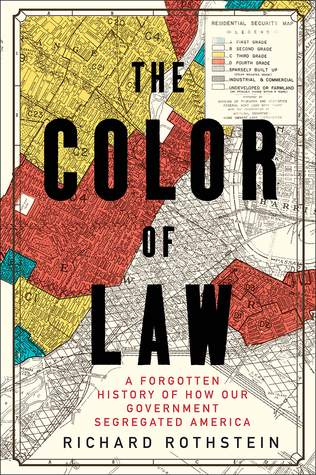

The Color of Law by Richard Rothstein was not what I expected, but then I’m not sure what that was. It reminded me of a dissertation, so it was not surprising to learn that the author was associated with the Economic Policy Institute, and was also working with multiple universities through fellowships. Then I read (in the acknowledgements, seriously, at least skim them in every title you read) that Ta-Nehisi Coates (yes, the author of The Water Dancer) reached out to the Economic Policy Institute to request Rothstein focus his state-sponsored segregation research on producing a book for the general public. This is that book, although I’m not certain it’s quite as accessible as was intended. Having majored in political science (albeit years and years ago), The Color of Law reminded me of several of my undergraduate classes that used case law and one of my political history classes (yes, I’ve taken a few, and those classes are only a part of the reason I love to debate). That said, those interested in the topic should definitely pick up this title, although I do not encourage readers to wait to begin it until only a couple of days before it is due back to the library (like I did, oops).

The goal of this book is to outline the intentional government actions that created systemic racism in the form of segregated neighborhoods that are still evident in most American cities.

“Taken in isolation, we can easily dismiss such devices as aberrations. But when we consider them as a whole, we can see that they were part of a national system by which state and local government supplemented federal efforts to maintain the status of African Americans as a lower caste, with housing segregation preserving the badges and incidents of slavery.”

I highly suggest readers experience The Color of Law for themselves and decide if they think the evidence achieves the goal. I’m convinced.

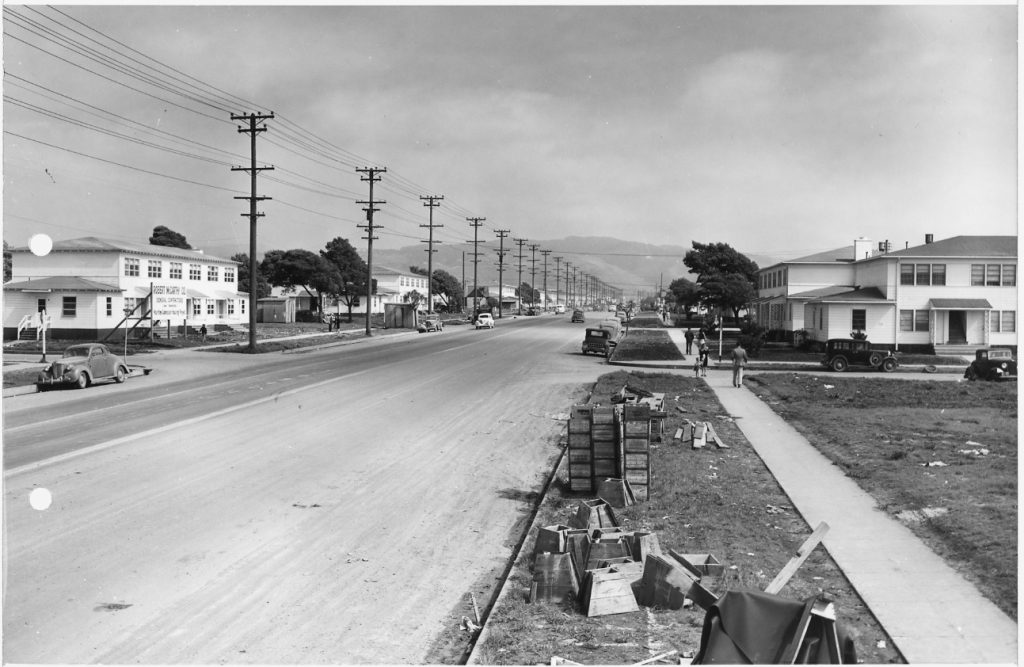

Image from Wikipedia

The Color of Law includes story after story, beginning in San Francisco during WWII. African American families and individuals moved to the area to participate in the war effort by working in shipyards and military industries. Housing was an issue because of the influx of workers, and African American workers were prohibited from purchasing homes because of the actions of the Federal Housing Administration and VA (refusing to insure loans), from neighborhood associations (HOAs) that added restrictive covenants, and from neighbors who were violent. There are also the actions of local school boards in deciding where to put schools that left them segregated decades after that was deemed unconstitutional by the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education. For anyone who might argue that schools are outfitted equally across counties, I encourage you to look at how schools are funded. Yes, the counties provide the bulk of the funds for the items they deem necessary, including teachers and textbooks, through property taxes, which are directly connected to the assessed value of homes within the county. Additionally, a great many items are purchased with funds Parent Teacher Organizations (PTOs) raise. Even in my affluent county, funds have to be raised by annual school fees for classroom supplies and by PTOs for library books, musical instruments, technology, and sometimes even building maintenance. Because of the average income of my area, this is a challenge not a problem, but what about those areas whose average incomes are close to poverty? How can they afford these items? What alternatives do these students and families have? Few to none actually.

I wonder how far we’ve come, remembering in 2009 when shopping for our first home, we discussed HOA restrictions with our Realtor who told of a client who’d purchased a house then got a promotion at work. That promotion included a company vehicle, and that vehicle meant the family had to move because it was considered a “work truck” by the HOA and was not allowed to be parked in the driveway, and overnight street parking was prohibited. This restriction has the outward appearance of wanting to maintain the appearance of the neighborhood, but in reality, it is discriminating against individuals who have blue collar jobs. Was it racially motivated? I don’t know, but it definitely feels class motivated, at the least. But wasn’t that an older restriction that wasn’t enforced because of its discriminatory nature? Well, it was enforced, and I’m fairly certain the neighborhood in question was built in the late 80s or early 90s, so no it wasn’t older.

There is also a section of The Color of Law on the housing crisis of 2008, which highlights several instances of legal action against lenders due to statistical significance of race and subprime mortgage terms. One example is the City of Memphis suing a lender, which included evidence of subprime loans being referred to as “ghetto loans.” As Rothstein points out, families who were foreclosed on during this crisis are no longer able to secure conventional loans, loans that many of those families could have qualified for when they purchased the home rather than depending on a subprime loan. “In 2000, 41 percent of all borrowers with subprime loans would have qualified for conventional financing with lower rates, a figure that increased to 61 percent in 2006.” They are now required to rent or to return to the abhorrent contract buying system of the 1960s which included high interest, unamortized (read: does not build equity) loans that must be paid in full before ownership is transferred. This removes any generational wealth that could have been accumulated. In most families, generational wealth is accumulated through home ownership. I remember hearing stories of all the houses my mom lived in growing up as my grandparents moved around the city, using real estate to build wealth, buying and selling at the right time. This started in the late 1940s and they continued to move around until the mid 60s when they purchased a goat farm and built two houses on the land, one to live in and one to sell. This meant that my grandmother could retire when she became too ill to work in the 80s, and that my grandfather could go part time and then retire when he decided to in the 90s, and they didn’t have to worry about money. They were the ones the rest of the family went to when we had a need we couldn’t afford, and then they argued about which account it would come from, not whether or not they would or could help. Their accumulated wealth, in part helped by the fact that their parents owned their homes and were financially independent until they passed away and passed down their wealth in the form of their homes, combined with their generosity, meant that my family can live in the home we now own (even though it is leveraged with a mortgage). If my skin was darker, as Rothstein says, my family would have had to work twice as hard, because my great-grandparents would have had to pay rent their entire lives, and my grandparents wouldn’t have been able to secure a loan to purchase any of their homes.

Image from the Othering & Belonging Institute

What can we do about this? Well, as Rothstein says, the first steps include learning about it and teaching future generations about our past, accurately. Then we need to work towards integrating society, which will be slow as we have a lot of work to undo. People are typically fearful about the unknown, and as many neighborhoods and communities are segregated, we have a lot of learning to do. Reading The Color of Law is one part of that, and one I’m glad I learned more about. It did not unveil any large-scale, new ideas to me, but did outline with great detail just how widespread systemic racism was and is with regard to housing, and with less detail, schools. The work ahead of our society is going to be hard.

Even with all I know, I am resistant to one of the measures Rothstein suggests. He says one “remedy would be a ban on zoning ordinances that prohibit multifamily housing or that require all single-family homes in a neighborhood to be built on large lots…” I live in a neighborhood of single family homes on large lots. The neighborhood started in the 70s and was the first in the area. We chose this neighborhood because of the lot size and the absence of an HOA, also it may have been the last affordable house in the town (to quote my husband). We chose this town because it was part farm community and part bedroom community, with many working adults commuting into the city. Now, several more farms have been sold off and are in the process of becoming single family neighborhoods (with small lot sizes and what I consider medium to large interior square footage – definitely not small). My understanding is there is also a prohibition on multi-family housing in the town. The closest we come is three complexes of town homes, two of which have been built in the last several years. (Ashley here: though townhomes do seem like they would be multi-family, they are traditionally a single family residences, with shared exterior spaces insured and managed by an HOA. Multi-family residential are two or more family units per tax record, duplex, triplex, quadplex, and small and large apartment complexes. #RealtorLife) I confess I want the farm community feeling back. I want people to stop complaining about the congestion these new homes have added to our town. I want increased class integration in our area, but I don’t want to add the number of people or vehicles multi-family housing would add. The population has grown faster than the roads and faster than the schools, and I have concerns about other infrastructures as well (water, sewer, electric grid, and internet access is definitely an issue, and that was before everyone started to work and learn from home). I too am part of the problem, but reading this book and learning more about our collective history is part of becoming an informed citizen. Now that I know, I can re-evaluate my previous thoughts, and seek to be a part of a complex solution to the long standing problem of segregation.

There are sections of the book that are repetitive as Rothstein drives home his points, but for readers who take more than a few days to read this, they may be less bothersome. Overall, I give The Color of Law four stars. It was well-researched, thorough, and detailed. The writing is academic, which lends itself well to the topic. I’m not likely to reread this title, although I may consult it for data, but I am interested in Rothstein’s backlist, much of which discusses public education.

And, if you’re interested in a quick podcast of thoughts about the challenges past policies and practices have yielded and considerations for the future, check out this TED Talks Daily from 6/30/2020 – How we can build sustainable, equitable cities after the pandemic with Vishaan Chakrabarti.

~Nikki

Image from DeirdreMask.com

When I picked up The Address Book by Deirdre Mask, I thought I was picking up something more akin to what Nikki read in The Color of Law. But, you know what, that’s my fault for not reading the marketing copy well, and I’m not remotely sad that I read the book. According to GoodReads I started and finished the book on June 22nd, so there wasn’t any struggle about reading it. (I mean, except that I, like Nikki, also only had a few days left on the loan from the library, also whoops.) Deirdre Mask is, according to her website, “a writer, a lawyer and sometime academic.” In the FAQs of her website, she explains that the curiosity of addresses began when she mailed her father a birthday card while she was living in Ireland, wondering why she paid Ireland for the postage even though the majority of the work of delivery was to happen in the United States. She found the website for the Universal Postal Union which became the jumping off point to follow Alice down the rabbit hole.

The main thesis of the book is held inside these two statements: 1) “Addresses aren’t just for emergency services. They also exist so people can find you, police you, tax you, and try to sell you things you don’t need through the mail.” and 2) “Street names, I learned, are about identity, wealth, and […] race. But most of all they are about power—the power to name, the power to shape history, the power to decide who counts, who doesn’t, and why.” The first is pretty self explanatory, governments want to know who lives where not only to tax you and the property owner, but to provide its constituents with the infrastructure that allows modern life to jaunt along at its merry pace – law enforcement, education, emergency services, utilities and roads, and political representation being several of the things that are dictated by the amount of residents in a location.

If you scan the table of contents (which I suggest you do for every book you read, but especially those nonfiction works where the structure of the book typically follows an academic progression), you will see that Mask designates five sections of her work from which you can easily jump to sections that focus on politics, race, or class and status. She covers the identity part of her thesis in the ‘development’ section, focusing on the slums of Kolkata where the lack of an address keeps people from applying for and receiving much needed government assistance and other markers of identity like government issued identification. Oh, the important things a seemingly ubiquitous item such as an address stops one from receiving. (Governments like to know who lives where, especially those who are not nationals. Every time we move Adam has to inform USCIS within 10 days or be subject to deportation. What is a more powerful thing than to be able to break up families because of bureaucracy?)

Mask doesn’t just focus on the race issues in America, where she talks about the streets named after confederate personalities in the south and the implications of neighborhoods with streets named after Martin Luther King, Jr. (Which is what I thought the entire book was going to be about, but it was the global meaning of an address rather than an American.) She also has an entire chapter on the post-apartheid issues in South Africa, which I think can be summed up in the following quotation.

Under apartheid, many of the street names were in the Afrikaans language, or honored Afrikaners, whose government had largely designed and implemented apartheid. The government hadn’t even bothered to give many of the nonwhite areas street names at all; even today, thousands of streets are unnamed in the country.

The Address Book: What Street Addresses Reveal about Identity, Race, Wealth, and Power is a global calling out of the power that is shown on a map. Did you know that in Korea and Japan they don’t typically name streets? The blocks between the streets are numbered and that has to do with the way their language is written! Did you ever think that we name streets because our language is written on a line, from left to right, rather than inside a box like the characters in Japanese and Korean? Now you do! Pick up this book to find out why street names are numbered, how houses got numbered, and why in America odd numbered buildings are on one side and evens on the other. It’s super fun to find out the why of things that are so normal as to be taken for granted.

Learning leads to being and doing better for everyone. Are there any books you have read lately that have hidden so much information and meaning to the way you look at the world?

~Ashley