The following post includes affiliate links. More details here.

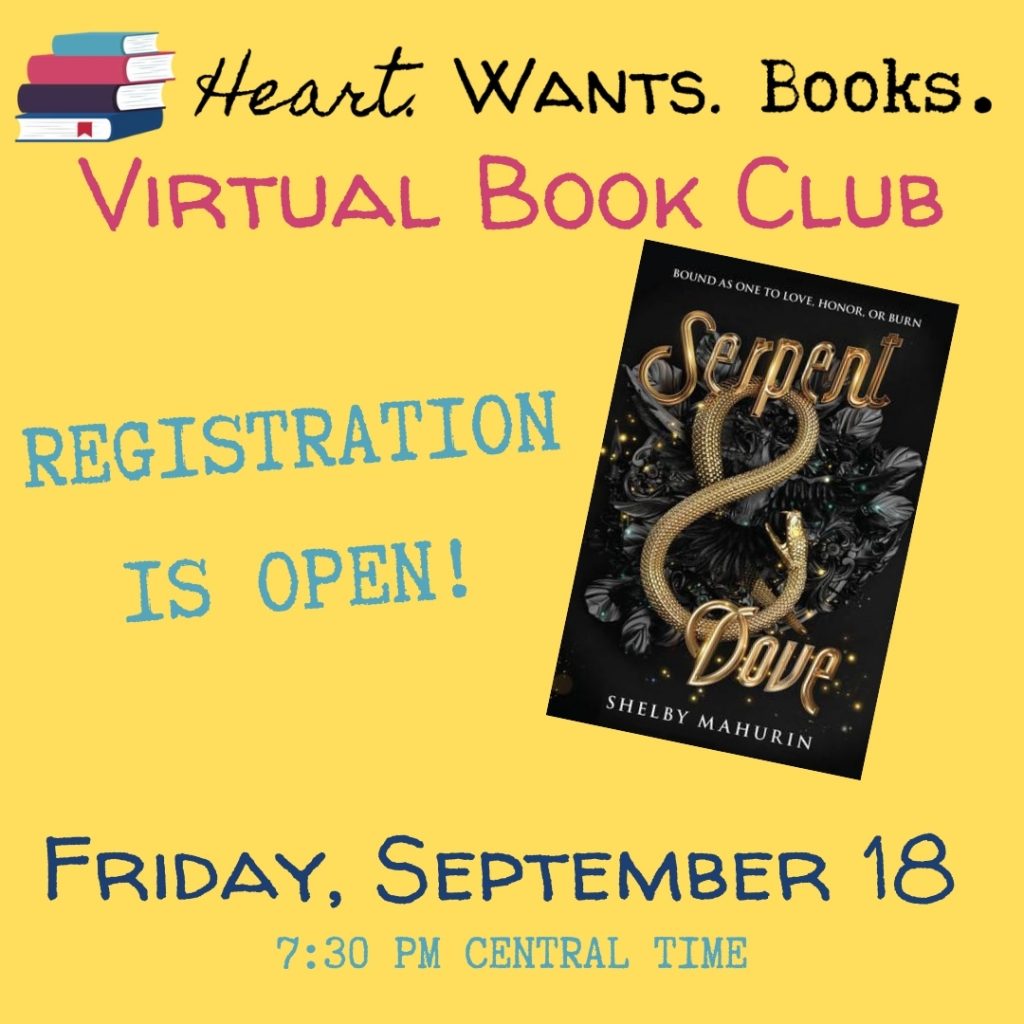

Before we bring you this week’s guest post, we want to share with you a notable Kindle sale: The Last Train to Key West by Chanel Cleeton, which we’ll be discussing on Thursday, is on sale for $1.99 right now (and also Next Year in Havana). It’s an interesting story, well-told. We’ll have more on Thursday, and until then, we give the floor to our dear friend, favorite gardener and book aficionado, the Cheap and Dirty Hoer.

Do you think you could eat only what you grew, raised, or could find locally for a whole year?

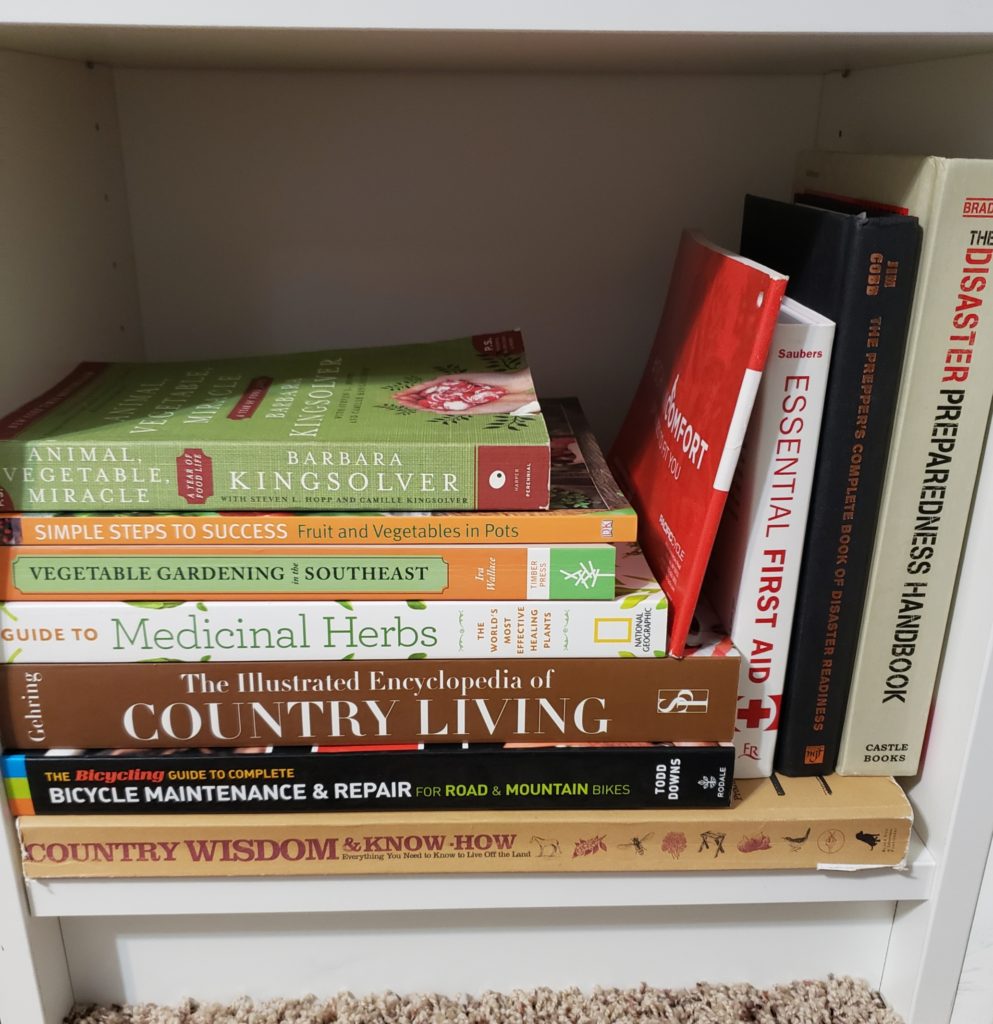

Animal, Vegetable, Miracle is the true story of a family’s decision to do just that. Author Barbara Kingsolver and her family—husband, Steven L. Hopp, and two daughters, Camille and Lily—made “every attempt to feed [themselves] animals and vegetables whose provenance [they] really knew,” with minor exceptions, as not all staples grow in Virginia, where their homestead is, and each family member was allowed to choose one splurge item. Steven chose coffee, which I’m thinking would be at the top of Nikki’s list, too [Nikki: confirmed, as I enjoy more. Ashley: ditto]. Kingsolver humbly says that, if Steven was given the choice between their family and coffee, “it might be a tough call.” RELATABLE AF.

Some of you may be wondering what a book about a bunch of locavores has to do with “survival,” the September theme here at Heart.Wants.Books. Or you may be thinking, “I’m not some pioneer woman; maybe I should skip this one.” Still others are saying, “Hey, you’re not Nikki or Ashley. Why should I listen to you telling me what to read?”

Patience. I will answer all your queries in the reverse order of when they were received.

Allow me to introduce myself, since this isn’t the Regency Era, and I can’t hand my card to your butler. (Alas!) I am The Cheap and Dirty Hoer: gardener, writer, reader, and friend of Nikki and Ashley. I purvey my foul-mouthed homesteading wisdom over at my own aptly named blog. Come see me if you like your plant advice mingled with memes and motherf—well, you get the idea.

As for all of you who bewail your black thumbs or simply aren’t into the green scene, you can still very much enjoy this book if you do one thing: eat. Animal, Vegetable, Miracle is for anyone who consumes food, so, unless you are from the future and get your nutrients in pill form (In which case, why on earth are you visiting 2020, of all years? If it’s for Taco Bell’s Mexican pizza, you’re too late.), I would encourage you to read this book. Not only is it relevant to something you do three times a day, give or take, but it’s beautifully written by a true wordsmith.

Millennials like me and the H.W.B. duo may remember Barbara Kingsolver’s name from their AP English reading list, attached to the novel that made her a household name (at least among those containing teachers or lovers of modern lit): a magnificent work called The Poisonwood Bible. I say “magnificent” because that is the impression that remains with me. High school was more than a hot minute ago, so I’m fuzzy on the details. Something about mission workers in Africa? I may not remember the plot, but the writing made an impact on me, and it was a good enough one that, when I later saw Kingsolver’s name on a book about a topic I liked (food), I thought it worth a go.

from her Goodreads

In case you’ve never heard of her, let me bring you up to speed. Not because this is a book report and that’s part of the formula, but because you should know her credentials, what qualifies her to write a book on this subject. But I’mma do it briefly because you may have ramen cooking (no judgment; that shit’s delicious): a master’s in ecology and evolutionary biology; New York Times bestseller (for every book since Pigs in Heaven in 1993); Pulitzer Prize finalist (for The Poisonwood Bible); raised in Kentucky, and then in The Congo (now the Democratic Republic of Congo), the latter without electricity or running water. That last bit is just so you know she isn’t some city girl who thought it would be cute to move to the country and play farmer.

I confess not only my admiration for Kingsolver’s work, but also my obvious predilection for the subject matter of Animal, Vegetable, Miracle, being as I am both an enthusiastic gardener and an advocate for responsible food production and consumption. I have a homesteading blog, I have been an officer in my local garden club, and I organize an annual seed share and expo for children and adults. When the latter was canceled the week of—due to the virus-that-shall-not-be-named —and the rest of the semester’s substituting assignments (my day job) were too when the schools closed in my state, I went straight to my greenhouse and got to work.

Since then, the greenhouse and garden have been my sanctuary, the one place I can find peace in the midst of chaos. When I enter that space, everything fades except for the sound of my shears snipping, the hum of the honeybees hovering inside the bellies of squash blossoms, and the intoxicating GREEN smell of a broken tomato branch.

As you can see, I can wax rhapsodic about plants, albeit with nowhere near the skill that Kingsolver does. She could make a toddler yearn for Brussels sprouts like they were candy, which is one thing that makes this book so compelling, regardless of your horticultural skills. Her love of food is apparent and contagious, as is her passion for sustainability and locavore culture. Interwoven with the personal narrative are data and facts, some of which might be upsetting—hopefully in a motivating kind of way.

Anything the family could not grow or obtain locally had to be purchased “through a channel most beneficial to the grower and the land where it grows,” because the aim was not to spend a year in misery without Doritos, but to really think about where their food came from. Humans expend a lot of fossil fuels so that they can have asparagus in September or tomatoes in January. Apart from the environmental impact—which neither Kingsolver nor I get preachy about, though it does matter—what we don’t realize is the impact this has on the quality of said food.

Have you ever wondered why grocery store produce can be so bland? A tomato should just be a tomato, right? It should taste the same no matter where we get it, we figure. But that winter tomato was doomed to be insipid from its inception. The produce we grow today is designed not for flavor and nutrition but for two things: storage and transportation. It has to be able to survive a journey of hundreds, if not thousands, of miles without spoiling or getting damaged, and then sit on a shelf, doing its best to look tempting while waiting to be taken home, like a lonely lady still at a bar for last call. This is why, as Kingsolver explains, we now eat just one percent of the vegetable varieties that were eaten at the dawn of the 20th century.

It is also the impetus for the heirloom seed movement. My husband HATED raw tomatoes until he tasted an heirloom variety I grew called Pruden’s Purple. It’s juicy and meaty, without a lot of “goop” inside, its color is alluringly vivid, and the flavor is everything a tomato dreams of being. They can be huge, too. One I grew this summer weighed over a pound a half; a single slice of it was enough to cover an entire BLT.

So why don’t you see these wonders in stores? A couple of reasons: One, they have a tendency to form what are called “shoulders,” where the skin rolls and puckers around the stem (again, relatable). These form weak spots where they can crack, and cracking leads to faster spoilage. Two, though their skins are no thicker than store-bought, their bottoms can form some amusingly-shaped rings that may cause some consumers to clutch their pearls.

Maybe this doesn’t alarm you. Maybe you aren’t saddened by the idea that you have been denied the pleasure of eating more than a handful of different food species, let alone the host of varieties they come in. Maybe you don’t have a sense of taste. So, why should this concern you? Google why banana flavor doesn’t taste like any banana you know, or why the American chestnut tree is hard to find, then we can talk.

If your ramen is starting to boil, I’ll save you the search: It comes down to the dangers of monoculture. Variety is what keeps a species going. It’s why mutts live forever and Great Danes only get an average of 8 years. (Bless the gentle giants.) There’s no telling what blight may strike or what pests may come seeking to devour. What will keep a species from disappearing altogether is having different versions of itself, some of which will turn out to be immune, for whatever genetic reason. That is how they survive. (Told ya’ I was gonna tie into the theme.)

Most of you are old enough to remember March. I know it was 193 Covid-years ago, but many of your grocery stores are still trying to stock their TP aisles. If the pandemic has done anything helpful, it’s shown us that we are highly dependent on every link in the supply chain. One tiny thing like a global outbreak can gum up the whole system, leaving you scouring your Safeway for butt paper, let alone taco fixins. For many of us, it also showed how much we depend on our neighbors, which is partly what eating local is about.

I’m fortunate enough to live in an agricultural area; I can drive down the road to buy produce just yards from where it was grown by people I share this community with. I know when you live in the city or even the suburbs it can be hard to connect with the idea of eating local because maybe the only plant your neighbors are growing is some devil’s lettuce, but the reasons you should do it are manifold. I’ll let Kingsolver explain all the whys and wherefores, but, if you’re ready to give it a go, you can start by finding a local farmer’s market here: https://www.localharvest.org/farmers-markets/. It’s nearing the end of the season, but it’s not too soon to think about next year, and many will still have lots of canned or dried goods, honey, or even meat. They may also be able to tell you where you can buy their products in winter. You may also consider signing up for a CSA (Community Supported Agriculture) program, some of which have fall/winter boxes. (That’s right! Did you know that some plants grow in winter?) Find one here: https://www.localharvest.org/csa/.

Kingsolver ties in a myriad of topics throughout, ranging from industrial agriculture to what cooking means for liberated women. My new aim in life is to be invited to a dinner party at their house, both for the stimulating conversation and the chow. Just look at what they fed their guests in Chapter 12: cucumber soup (made with homemade yogurt), grilled vegetable panini (squash, peppers, eggplant, onions, homemade mozzarella, fresh herbs, fresh baked bread), “Disappearing Zucchini Orzo,” and cherry sorbet. Hashtag GOALS.

I don’t want you to come away from this with the impression that Animal, Vegetable, Miracle is a sermon of sorts, because it truly isn’t. It’s a joy to read, which is why I think she chose the last word of the title. While Kingsolver is clear about what camp she’s in, her aim wasn’t to browbeat everyone into coming over to her side. Animal, Vegetable, Miracle reads more like an ode to nature in general, and food in particular. Side by side with the informative blurbs are family recipes by her older daughter, Camille, and humorous anecdotes about the struggles the family faces throughout the seasons, like when younger daughter Lily’s flock turns out to be half roosters and try crowing for the first time, making it clear that none of them would have a chance of winning Ameraucana Idol. (That pun is hella funny to chicken people.)

Whether you’re a gung-ho gardener like me or succulents make you break out in a nervous sweat [Nikki: like me], you can find something to enjoy in Animal, Vegetable, Miracle. And if you enjoy it, you might want to check out Kingsolver’s fiction works, including Prodigal Summer, which weaves in romance and family drama with that history of the American chestnut I hinted at earlier.

If I hadn’t read Animal, Vegetable, Miracle, I would still be ignorant of the fact that there is such a thing as a Dog Pecker morel mushroom, so there’s that… (Don’t google it. No, wait—DO.)

~Cheap and Dirty Hoer

You can find more sass gardening and homesteading advice from The Cheap and Dirty Hoer here, where you can also subscribe, and give it a follow here.